Carved into Mount Rushmore and the history books as a legendary figure and one of America’s founding fathers, George Washington made his way to the presidency after an epic win at the Battle of Yorktown, which gave the United States the independence it had sought from England for years.

The word epic is often overused as hyperbole by a certain subset of pop culture aficionados in the United States, but it is perhaps the single best describer for the nation’s most celebrated liberator: Hero, icon, myth of star-spangled awesomeness.

The war general largely credited with delivering victory in the American Revolution was a truly remarkable figure, full of virtuosity and mythological status as one of the best and fairest governors of the land.

In brief, here are five things you might not have known about the nation’s first president:

The Father of His Country

Washington Crossing the Delaware. (Wikimedia Commons)

That was the patriarchal nickname granted to Gen. Washington after his critical roles in the Revolutionary War and Constitutional Convention.

According to historians at Mount Vernon, the estate of Washington, this nickname first made its association with George as early as 1776. He received a letter the following year from Henry Knox, stating,”the People of America look up to you as their Father, and into your hands they entrust their all.”

The first elections would not be held until 12 years later, however, when the electoral college unanimously elected him as president for two consecutive terms — a feat that has not since been replicated.

He was a party unto himself

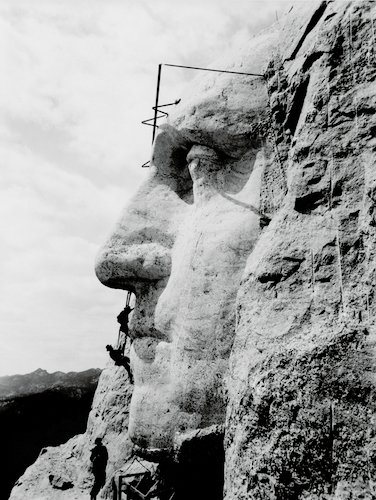

Construction at Mount Rushmore of George Washington’s likeness. (Wikimedia Commons)

Washington had actually hoped that no political parties would be formed in the United States and was thus not a part of any one faction, instead relying on his wits, fairness and experiences from the battlefield to lead the national government through its first years of existence.

In his sprawling 7,641-word Farewell Address, Washington warned against “the baneful effects of the Spirit of Party,” and urged compatriots to resist the dystopic duopoly of a partied political system in favor of a more independent government.

“It serves always to distract the Public Councils, and enfeeble the Public Administration,” warned Washington. “It agitates the Community with ill founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another; foments, occasionally, riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions.”

He’ll never be outranked in the U.S. Military

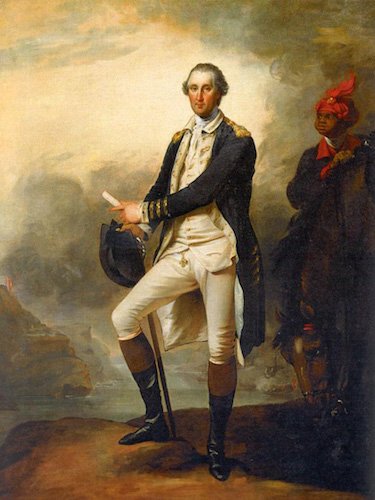

Portrait of George Washington and William “Billy” Lee. (Wikimedia Commons)

General of the Armies of the United States.

That’s the title earned by Washington posthumously in 1976, after a historical review of his accomplishments on the battlefields of the French and Indian War and Revolutionary War, where his opposition of Lord Charles Cornwallis in concert with French Admiral François Joseph Paul de Grasse helped him launch the “free world” as we know it, and later become an honorary French citizen.

When Cornwallis surrendered his 7,000-plus troops to Washington, the British band played “The World Turned Upside Down” as peace negotiations were prepared for 1782.

Washington’s efforts generated a position of general higher than any rank currently offered by the U.S. military.

He wasn’t an overly religious person

Flickr/Wonderlane

In a retrospect with noted historian Edward Lengel, author of “Inventing George Washington,” NPR documented the fact that the first president wasn’t the type to carry around the Holy Bible and reference it on the battlefield a la Gen. George S. Patton.

“He was a very moral man. He was a very virtuous man, and he watched carefully everything he did,” says Lengel. “But he certainly doesn’t fit into our conception of a Christian evangelical or somebody who read his Bible every day and lived by a particular Christian theology.”

“We can say he was not an atheist on the one hand, but on the other hand, he was not a devout Christian.”

He was very, very wealthy

“Lady Washington’s Reception Day” by Daniel Huntington. (Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to commanding a paycheck that amounted to 2 percent of the federal budget, Washington’s property holdings were not only highly valuable but also profitable due to the production on the property.

Indeed, Washington owned in upward of 300 slaves and even had a whiskey distillery installed on Mount Vernon that produced some 12,000 gallons a year. The 7,000-acre estate was worth $800,000 at the time he died – almost $15 million in today’s money – and until Donald Trump’s election in 2016 he was considered the wealthiest man to ever board up in the White House, a place on the Potomac he personally oversaw the development of.

America’s favorite father was also a tobacco farmer in his middle age, and he ensured all public appearances pointed toward wealth, even demanding a chariot “made in the newest taste, handsome, genteel and light … on the harness let my crest be engraved.” Although he had no children of his own to pass off an inheritance to, he adopted his wife Martha’s children from a previous marriage and raised them as his own.